Bitcoin $BTC▲4.15% is nearing one of its most important milestones: The Halving (or Halvening), an automated event that cuts the monetary reward for mining BTC by 50%.

Depending on who you believe, Halvings either cause Bitcoin‘s price to skyrocket, its hash rate to crash, or simply exist as a relatively boring exercise in economic theory.

[Read: Gambling on Bitcoin with Trump’s $1,200 corona check was a good bet]

Rather than debate whether the market has already “priced in” the next Halving (which should happen sometime early on 12 May 2020), let’s explore why Bitcoin‘s mysteriously absent creator decided Halvings should occur at all.

Unlike fiat money, which can essentially be created out of thin air, Nakamoto set the upper limit for Bitcoin’s supply to 21 million — once the network reaches that number, no more BTC can ever exist.

Since 2016, the Bitcoin network has reimbursed miners for validating transactions with 12.5 BTC ($123,500). This is meant to cover the costs associated with the computer equipment required to efficiently mine Bitcoin.

Within the next few days, that number will shrink to just 6.25 BTC ($62,125), a change that will have two effects on the ecosystem: Bitcoin‘s scarcity will increase, while the Bitcoin-earning potential for miners shrinks.

But mining rewards are simply Bitcoin‘s way of balancing the threat of inflation with distributing new coins.

In fact, scheduling Halvings every four years is Satoshi Nakamoto‘s way of nurturing value growth by keeping the circulating supply of BTC in line with adoption.

Nakamoto explained this thought process in an email:

The fact that new coins are produced means the money supply increases by a planned amount, but this does not necessarily result in inflation. If the supply of money increases at the same rate that the number of people using it increases, prices remain stable. If it does not increase as fast as demand, there will be deflation and early holders of money will see its value increase.

Coins have to get initially distributed somehow, and a constant rate seems like the best formula.

Simply put, if Nakamoto had made the full 21 million supply of BTC available upon launch, supply would’ve far exceeded demand, and its value would’ve had very little chance of rising.

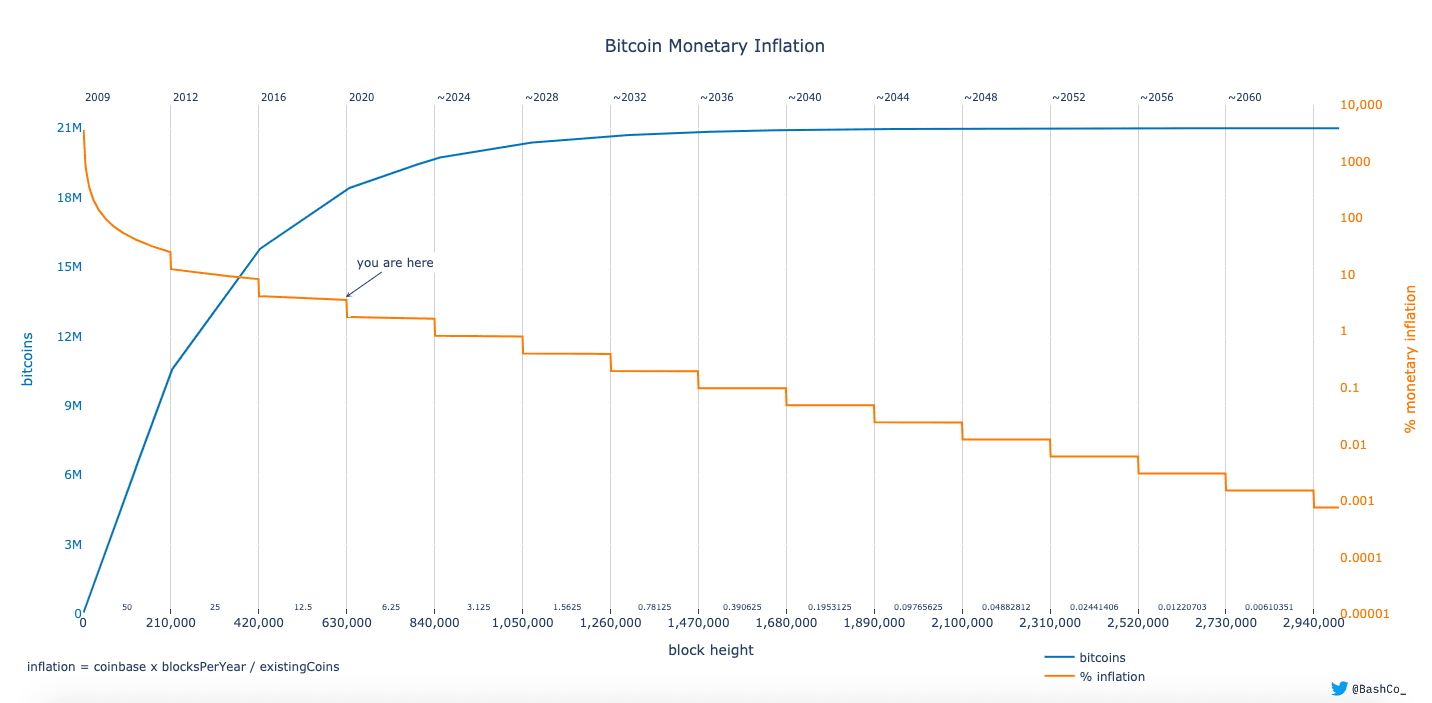

The graph below should help you visualize this process. It charts Bitcoin Halvings (in orange) against the total number of Bitcoins in circulation (in blue).

Nakamoto strategically set “dates” for Bitcoin‘s Halvings on a logarithmic scale. The orange line, which denotes monetary inflation, steps down at even intervals, while the blue line (circulating BTC) shoots up in the beginning but tapers sharply.

This shows that even though the Bitcoin network released more than 85% of Bitcoin‘s overall supply in its first 10 years, the final Bitcoin won’t be mined until 2140.

As for what happens after: miners will be restricted to recouping their upkeep costs by collecting network fees only. Right now, network fees equate to less than 5% of the current block reward (on average).

Before you’re tempted to imagine how viable that might be for the network, remember that this reality won’t hit for another century (at least). Odds are the inflationary status of Bitcoin won’t carry much importance for you by then, so no worries.