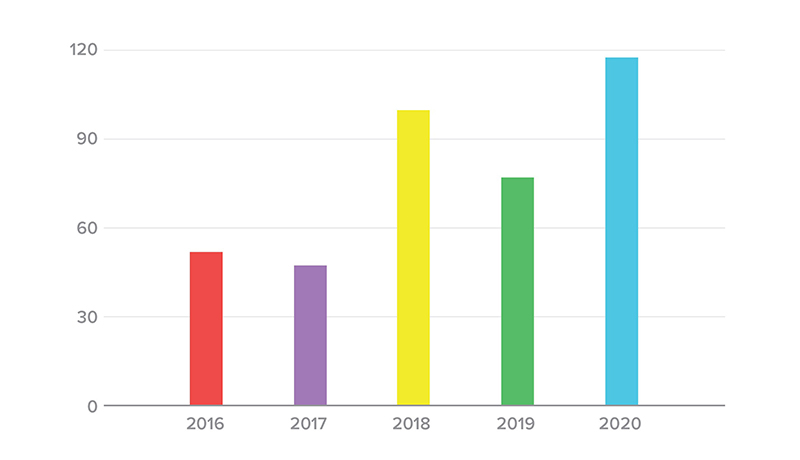

The number of annual credential spill incidents nearly doubled from 2016 to 2020, according to F5’s latest Credential Stuffing Report.

Released today, the most comprehensive research initiative of its kind reported a 46% downturn in the volume of spilled credentials during the same period. The average spill size also declined, falling from 63 million records in 2016 to 17 million last year. Meanwhile, the 2020 median spill size (2 million records) represented a 234% increase over 2019 and was the highest since 2016 (2,75 million).

Credential stuffing, which involves the exploitation of large volumes of compromised username and/or email and password pairs, is a growing global problem. As a directional case in point, a Private Industry Notification issued by the FBI last year warned that the threat accounted for the greatest volume of security incidents against the US financial sector between 2017 and 2020 (41%).

“Attackers have been collecting billions of credentials for years. Credential spills are like an oil spill, once leaked, they are very hard to clean up because credentials do not get changed by unassuming consumers, and credential stuffing solutions are yet to be widely adopted by enterprises. It is not surprising that during this period of research, we saw a shift in the number one attack type from HTTP attacks to credential stuffing. This attack type has a long-term impact on the security of applications and is not going to change any time soon,” said Sara Boddy, Senior Director of F5 Labs. “If you are worried about getting hacked, it’s most likely going to occur from a credential stuffing attack.”

Sander Vinberg, Threat Research Evangelist at F5 Labs, and report co-author, urged organizations to remain vigilant.

“While it is interesting that the overall volume and size of spilled credentials fell in 2020, we should definitely not celebrate yet,” he warned “Access attacks – including credential stuffing and phishing – are now the number one root cause of breaches. It is highly unlikely that security teams are winning the war against data exfiltration and fraud, so it looks as though we’re seeing a previously chaotic market stabilize as it reaches greater maturity.”

Despite a growing consensus on industry best practices, one of the report’s key findings is that poor password storage remains a perennial problem.

Although most organizations do not disclose password hashing algorithms, F5 was able to study 90 specific incidents to give a sense of the most likely credential spill culprits.

Over the past three years, 42.6% of the credential spills had no protection and the passwords were stored in plain text. This was followed by 20% of credentials related to the password hashing algorithm SHA-1 that were ‘unsalted’ (i.e., lacking a unique value that can be added to the end of the password to create a different hash value). The ‘salted’ bcrypt algorithm was third with 16,7%. Surprisingly, the widely discredited hashing algorithm, MD5, accounted for a small proportion of spilled credentials even when the hashes were salted (0.4%). MD5 has been considered weak and poor practice for decades, salted or not.

Another notable observation in the report is that attackers are increasingly using ‘fuzzing’ techniques to optimize credential exploit success. Fuzzing is the process of finding security vulnerabilities in input-parsing code by repeatedly testing the parser with modified inputs. F5 found that most fuzzing attacks occurred prior to the public release of the compromised credentials, which suggests that the practice is more common among sophisticated attackers.

In the 2018 Credential Stuffing Report, F5 reported that it took an average of 15 months for a credential spill to become public knowledge. This has improved in the past three years. The average time to detect incidents, when both the incident date and the discovery date are known, is now around eleven months However, this number is skewed by a handful of incidents where the time to detect was three years or longer. The median time to detect incidents is 120 days. It is important to note that spills are often detected on the dark web before organizations disclose a breach.

The announcement of a spill typically coincides with credentials appearing on Dark Web forums. For the 2020 Credentials Stuffing Report, F5 specifically analyzed the crucial period between the theft of credentials and their posting on the Dark Web.

Researchers conducted a historical analysis using a sample of almost 9 billion credentials from thousands of separate data breaches, referred to as ‘Collection X’. The credentials were posted on Dark Web forums in early January 2019.

F5 compared Collection X credentials to the usernames used in credential stuffing attacks against a group of customers six months before and after the date of announcement (the first time a credential spill becomes public knowledge). Four Fortune 500 customers were studied – two banks, a retailer, and a food and beverage company – representing 72 billion login transactions over 21 months. Using Shape Security technology, researchers were able to ‘trace’ stolen credentials through their theft, sale, and use.

Over the course of 12 months, 2.9 billion different credentials were used across both legitimate transactions and attacks on the four websites. Nearly a third (900 million) of the credentials were compromised. The stolen credentials showed up most frequently in legitimate human transactions at the banks (35% and 25% of instances, respectively). 10% of the attacks targeted retail, with around 5% focusing on the food and beverage business.

Based on the study, the 2020 Credential Stuffing report identified five distinct phases of credential abuse:

“Credential stuffing will be a threat so long as we require users to log in to accounts online,” added Boddy. “Attackers will continue to modify their attacks to fraud protection techniques, which is creating a strong need and opportunity for adaptive, AI-powered controls related to credential stuffing and fraud. It is impossible to instantaneously detect 100% of the attacks. What is possible is to make attacks so costly that fraudsters give up. If there is one thing that holds true across the worlds of cybercriminals and businesspeople, it is that time is money.”